Jennifer Davis Michael was my English professor and advisor at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. She adeptly taught us how to think about and analyze poetry in her Studies in Poetry seminar and all manner of 18th- and 19th-century British literature in her Classicism & Romanticism classes, in which I thought of her primarily as a scholar of William Blake. In the two decades since my college graduation, I’ve kept up with Jennifer as a friend, and even more recently, I’ve come to know her as a poet in her own right. It is from these dual vantage points as student and friend that I read — and re-read — Jennifer’s poetry collection, Dubious Breath.

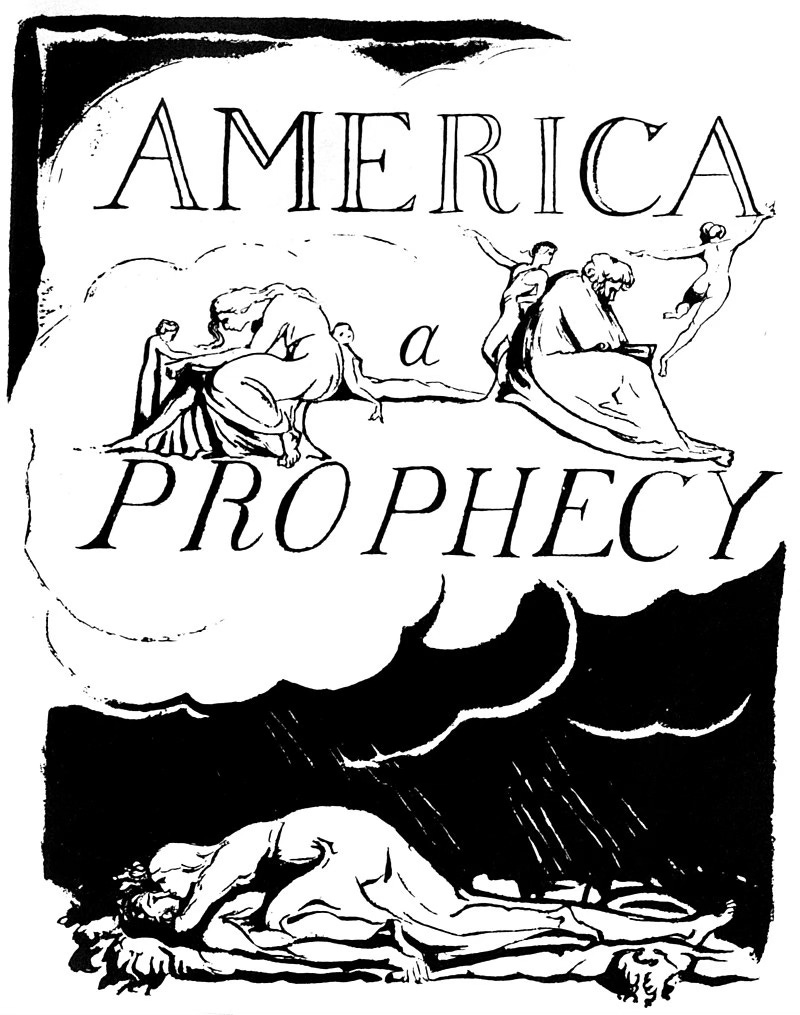

One fall day in 2020, her family and mine gathered around the firepit in her front yard. Unlike on so many other visits, we offered no hugs or handshakes so that we might spare each other the unseen – or unknown – exposure to the virus. From a distance we waved as we took our seats in folding camp chairs in the chilled air of the Cumberland Plateau. We gingerly poured wine into each other’s plastic glasses at arm’s length. We smiled through our cloth masks before we knew to wear KN95s or N95s. True to form, Jennifer donned one bearing a chilling image from William Blake’s “America: The Prophecy.”

That freeze-frame memory could be an image from Michael’s second collection of poetry, much of which entails new rituals such as ours created out of anxiety of what’s carried on our dubious breath. In these lines, for example, there is no exchanging of the peace, no communion: “We dare not even break bread in church.” A visit to the speaker’s father is “my phone / a window to his room.” Disembodied, the speaker returns to the reality of her neighborhood for a walk: “When friends pass by, I wave, / palming the empty air.” The air is rife with threat of contagion, but the distance from her father and her friends ensures safety for all.

While Michael’s poetry grapples with the tension between fear and safety, this collection, comprised of both new and previously published poems, is an antidote for the virus and its accompanying, pervasive fear.

There is certainly not enough distance for comfort in “Annunciation, March 2020,” in which the speaker and her family are huddled in their house during a tornado warning. Seemingly breathless through enjambment from the penultimate stanza into the last, she says:

Whatever is revealed tonight…. //

must be inside the cramped closets and bathtubs where we crouch with those we love, inhaling each other’s dubious breath.

Seeking haven from a storm ironically puts this family into even graver danger. The storm may have spared the lintels of their door frames, but what contagion on their dangerous breath puts them at risk while harboring from the storm? Which is worse, the tornado, so easy to visualize and hear, or the invisible, anxiety-producing virus?

In “Physical,” the speaker expresses the same dual anxiety about her body during a visit to the doctor. Each couplet details the perceived failings of another bodily system. One example:

My doctor’s stethoscope against my chest hears bullets puncturing a classroom door.

Will the doctor’s tools reveal the speaker’s fear, anxiety, and perhaps hypertension over yet another pandemic, that of school shootings?

In another couplet, the fear of failing vision:

My doctor has me read a foggy chart, the letters melting faster than the ice.

The fear of losing sight is presaged in the collection’s first poem “And in Those Last Days.” The poet, reflecting on a recent visit to the optometrist's office, juxtaposes the impossibility of choice: “Seduced by clarity, you opt for one, / but later long, with aching eyes, for the blur.” Too much clarity of vision and precision hurts.

And, of course, breath itself is at the heart of Michael’s poetic concerns. In “Pentecost,” the speaker expresses vexation:

When virus-laden breath rhymes perfectly with death, how dare we even pray for holy inspiration?

And while the spirit descends even though the “images are tired,” that won’t suffice during a pandemic, for a “world that’s sterilized / of spirit is unbearable.” Inspiration itself – a spirit’s filling us with breath – has become a deadly act. Our old symbols fail us, and life-giving breath now brings us death, a morbid rhyme.

And yet, the fear and anxiety are gradually alleviated. In the final line of “Savanna,” the very next poem, there is a glimmer of sanctification after a burn: “yes, we are here / preserved by fire.” The doctor in “Physical” also relieves the tension. He “draws some blood and says, you’re fine.”

More hope abounds in the final stanza of the last poem, “And Then.” There is assurance that everything will be fine, just like the doctor says. Even the poem’s title pushes us into the future, beyond this dubious moment. Michael flips the expectation of the air we breathe to an experience of touch, thereby reinvigorating the vapor, once rife with death:

…the air is so mild, the current so gentle, it holds you, benevolent, like a lover’s hand on your back, a child’s trusting grasp.

It is indeed very good. Bringing Michael’s guide to the pandemic to a close, the final stanza of “And Then,” and of the whole book, assures us that:

It holds. In this still moving, everything is held. It is weather, and more than weather. And it is very good.

The tempest stops, and the air allows us once again to breathe freely.

The masks drop, and we embrace around the firepit.

"My doctor’s stethoscope against my chest hears bullets puncturing a classroom door" really cuts. I love "It is held," and your final sentence describing how she moves from fear to hope. I went to Sewanee with Jennifer and have another book of her poetry. Looking forward to this one. Thanks for reviewing it.